Written by Jason S Jowett, sourced from historical fact. This blog may not be reproduced on whole without the authors express permissions. Copyright © 2023. Historical blog ~ thanks to Google.

Sunday, January 10, 2021

Monday, December 28, 2020

Rurik’s Kievan Rus’; Russian-Viking origin

Nestor's Chronicle or The Chronicle of Nestor, is a history of the Kievan Rus' from about 850 to 1110, originally compiled in Kiev about 1113 by Nestor (c. 1056 – c. 1114); hence scholars refer often to Nestor's Chronicle or of Nestor's manuscript as the source of Russian history. The original compilation now lost, was produced at the court of Sviatopolk II of Kiev (ruled 1093–1113), likely bearing Sviatopolk's Scandinavian allegiances. Nestor's Pan-Scandinavian attitude was confirmed by a Polish historian and archaeologist Wladyslaw Duczko, and he argued that the central aims of the Chronicle’s narrative was to ‘give an explanation how the Rurikids came to power in the lands of the Slavs, why the dynasty was the only legitimate one and why all the princes should terminate their internal fights and rule in peace and brotherly love’. Later accounts are the Laurentian Codex compiled by the Nizhegorod monk Laurentius for the Prince Dmitry Konstantinovich in 1377, which details the Russian periods until 1305, whilst the years 898–922, 1263–83 and 1288–94 are missing in context. Whereas the Laurentian (Muscovite) text traces the Kievan legacy through to the Muscovite princes. Another, the Hypatian traces the Kievan legacy through the rulers of the Halych principality. The Hypatian codex was rediscovered in Kiev in the 1620s written in Church Slavonic language.

The Primary Chronicle (Nestor's) describes the Rurik dynastic origin while accosted by the Tributaries of the Varangians (Vikings), “There was no law among them, but tribe rose against tribe. Discord thus ensued among them, and they began to war one against another. They said to themselves, "Let us seek a prince who may rule over us and judge us according to the Law." They accordingly came from overseas to the Varangian Russes: these particular Varangians (Vikings) were known as Russes, just as some are called Swedes, and others Normans, English, and Gotlanders, for they were thus named. The Chuds, the Slavs, the Krivichians, and the Ves' then said to the people of Rus', "Our land is great and rich, but there is no order in it. Come to rule and reign over us." They thus selected three brothers, with their kinsfolk, who took with them all the Russes and migrated. The oldest, Rurik, located himself in Novgorod; the second, Sineus, at Beloozero; and the third, Truvor, in Izborsk. On account of these Varangians, the district of Novgorod became known as the land of Rus”. The account is precluded by a vast narrative traced back to the descendants of Noah; Shem, Ham and Japeth, with the latter's descendants being Varangians, Swedes, Normans, and the Russians. Andrew the Apostle charted the Slavic migrations in detail surrounding the River Danube, as running east to west and straight across Eastern Europe, in addition to the western source of the Danube which was also the source of the Vistula river running north to south and reaching the Black Sea across modern Poland.

In AD 860, Rurik, the Varangian chieftain of the Rus' who maintained control of Ladoga, drove his kinsmen, the Vikings, back beyond the sea in refusing them further tribute. His port at Lagoda was a key strategic entry to the Balkans linking Kiev with Constantipole to which his descendants would take arms. The Greek-Arabic trade goods flowed along this route by the Dniester or Dnieper rivers, an alternative to the western route via the Vistula. The Russians so set out to govern themselves under Rurik I who remained in power until death in 879. Rurik bequeathed his realm to Oleg, who belonged to his kin, and entrusted to Oleg's hands his son Igor, who was too young to rule. At the time and according to Olof von Dalin, Askold (as Asleik Bjornson (Diar)), was the son of Björn Ironside, who ruled over Kiev with Dir. Accounts later relayed askold Dir as termed by the Rus' of their first Kievan ruler, whether in kind, meaning 'strange'. The Primary Chronicle details; Oleg set forth, taking with him many warriors from among the Varangians, the Chuds, the Slavs, the Merians and all the Krivichians. He thus arrived with his Krivichians before Smolensk, captured the city, and set up a garrison there. Soon he went on to capture Lyubech, before arriving at the hills of Kyiv. Here he saw how Askold and Dir reigned and so schemed to take control. Hiding his warriors in their boats, he went forward in a peaceful approach to Askold and Dir bearing the child Igor as any stranger on his way to Greece on an errand. Though on summons to which Askold and Dir responded his soldiers emerged, when Oleg denounced him and bringing forward Igor who Oleg proclaimed as the son of Rurik. Askold and Dir, were carried off to the Hungarian hill, executed and buried there, where the castle of Ol'ma now stands. Igor the heir of Rurik would twice besiege Constantinople in 941 and 944, via the Kyiv stronghol and although Greek fire destroyed part of his fleet, he concluded a favorable treaty in 945 with the Eastern Roman Emperor Constantine VII. In 913 and 944 the Rus' plundered the Arabs in the Caspian Sea during the Caspian expeditions of the Rus'. The Byzantines consequently accounted for Igor’s torture and death while collecting tribute from the Drevlians in 945. The Primary Chronicle points out that he attempted to collect tribute for a second time in a month. Igor's wife, Olga of Kyiv, avenged him by punishing the Drevlians and mandated a new legal system of tribute gathering (poliudie) as a result.

It was the Polyanians (Ukrainian: Поляни, Polyany, Russian: Поляне Polyane, Polish: Polanie) indeed who had built Kiev and named it after their ruler, Kyi. Polyanians were an East Slavic tribe between the 6th and the 9th century, which inhabited both sides of the Dnieper river, east of the Black Sea, running from Liubech to Rodnia and also down the lower streams of the rivers Ros', Sula, Stuhna, Teteriv, Irpin', Desna and Pripyat. In the Early Middle Ages there were two separate Slavic tribes bearing the name of Polans, one being the eastern, and the other being the western Polan, a West Slavic tribe. The name Polan is derived from the Old East Slavic word поле, meaning ‘field’, as according to the Primary Chronicle, such was entitled to those who lived in their fields and hence as farmers, the people were, whilst dependent on water for their crops, not necessarily so on the direct yields from the riverbanks nor it's boatmen. In the 9th and 10th centuries the Polans had well-developed arable land Farming, Cattle-breeding, Hunting, Fishing, Wild-hive Beekeeping and various handicrafts such as Blacksmithing, Casting, Pottery, Goldsmithing, etc. Thousands of (pre-Polan) kurgans, found by archaeologists in the Polan region, indicates their land had a relatively high population density too. They lived in small families in semi Dug-outs ("earth-houses") and wore homespun clothes and modest jewelry. Before converting to Christianity, the inhabitants used to burn their dead and erect kurgan-like embankments over them. Concerning the nomenclature of the distinct languages emergent during the Middle Ages; Ruthenian or Old Ruthenian is one source for a split, where in modern texts, the language in question is sometimes called "Old Ukrainian" or "Old Belarusian" (Ukrainian: Староукраїнська мова) and (Belarusian: Старабеларуская мова). As Ruthenian always bore a diglossic opposition to Church Slavonic, the vernacular language was and still is often called prosta(ja) mova (Cyrillic проста(я) мова), literally as ‘simple speech’.

Under the rulership of Emperor Heraclius, many of the Slavs were invaded and oppressed by the Bulgars, Avars, and Pechenegs. The Slavs from the Dnieper fell under the lordship of the Khazars of whom had had command of Kiev preceding the Rus', and were required to pay tribute. By the middle of the twelfth century, Kievan Rus′ had dissolved into independent principalities, each ruled by a different branch of the Rurik dynasty. Conflict was yet integral, such as Mstislav Vladimirovich’s campaigns, one of the earliest attested princes of Tmutarakan and Chernigov in Kievan Rus. He was a younger son of Vladimir the Great, Grand Prince of Kiev. His father appointed him to rule Tmutarakan, an important fortress by the Strait of Kerch, in or after 988. Subsequently he invaded the core territories of Kievan Rus, which were ruled by his brother, Yaroslav the Wise (978 – 1054), in 1024. Although Mstislav could not take Kiev, he forced the East Slavic tribes dwelling to the east of the Dniester River to accept his suzerainty. Yaroslav the Wise also accepted the division of Kievan Rus' along the river after Mstislav had defeated him in a battle fought at Listven by Chernigov (presents-day Chernihiv, Ukraine). Mstislav transferred his seat to the latter town, and became the first ruler of the principality emergent.

The Rurik dynasty underwent a schism after the death of Yaroslav the Wise in 1054, dividing into three branches on the basis of descent from three successive ruling Grand Princes: Izyaslav (1024–1078), Svyatoslav (1027–1076), and Vsevolod (1030–1093). In the 10th century the Council of Liubech made some amendments to the rules of succession and so divided Ruthenia into several autonomous principalities that had equal rights to obtain the throne of Kiev. The Rurik dynasty (or Rurikids) ultimately became the Tsardom of Russia whilst the last Rurikid to rule Russia, Tsar Vasily IV (from the House of Shuysky, cadet branch of the House of Rurik), reigning until 1610; Vasily Tatishchev referred to the Loachim Chronicle in referencing his own legacy as partisan to the Wends (Old English: Winedas; Old Norse: Vindr; German: Wenden, Winden; Danish: vendere; Swedish: vender; Polish: Wendowie).

Wednesday, January 10, 2018

Rome: Tetrarchy, the Nicene Council, & Orthodox Church

When the first Roman Emperor, Augustus (reigned 27 BC – 14 AD), transformed the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire in 27 BC, he reformed the office of Prefect at the suggestion of his minister and friend Maecenas. Again elevated into a magistracy, Augustus granted the praefectus urbi all the powers needed to maintain order within the city but even more so, to the ports of Ostia and the Portus Romanus, as well as a zone of one hundred Roman miles (c. 140 km) around the city. The Prefect was superintendent of all guilds and corporations (collegia), and held responsibility (via the praefectus annonae) for the city's welfare system.

A Prefect maintained direct authority through the cohortes urbanae, Rome’s police force (within independent prefecture - vigiles, praefectus vigilum). The Prefect needfully published the laws promulgated by the Emperor. Gradually, the judicial powers of the Prefect expanded. Eventually there was no appealing the Prefect’s sentencing, except to the Roman Emperor a reach over even all the governors of the Roman provinces. Originally the Prefect’s powers were exercised in conjunction with those of the quaestors, but by the 3rd century, the Prefect’s control was total.

In late Antiquity, the office of the Prefect gained freedom from the emperor's direct supervision as the Imperial court was removed from the city. The office was usually held by leading members of Italy's senatorial aristocracy, who remained largely pagan even after Emperor Constantine's conversion to Christianity. Over the following thirty years, Christian holders were few. In such a capacity, Quintus Aurelius Symmachus played a prominent role in the controversy over the Altar of Victory in the late 4th century.

The urban prefecture survived the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and remained active under the Ostrogothic Kingdom and well after the Byzantine reconquest.

Each of the tetrarchs themselves often were at work within the province or eparchy, while delegating most of the administration to the hierarchic bureaucracy headed by his respective Pretorian Prefect, each supervising several Vicarii, the governor-generals in charge of the civil diocese. The four tetrarchic capitals of the time were Nicomedia in northwestern Asia Minor (modern Izmit in Turkey), a base for defence against invasion from the Balkans and Persia's Sassanids. Sirmium (modern Sremska Mitrovica in the Vojvodina region of modern Serbia, and near Belgrade, on the Danube border) was the capital of Galerius, the eastern Caesar; this was to become the Balkans-Danube prefecture Illyricum. Mediolanum (modern Milan, near the Alps) was the capital of Maximian, the western Augustus; his domain became "Italia et Africa", with only a short exterior border. Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier, in Germany) was the capital of Constantius Chlorus, the western Caesar, near the strategic Rhine border; it had been the capital of Gallic emperor Tetricus I. This quarter became the prefecture Galliae.

The tetrarchy lasted until c. 313, when internecine conflict eliminated most of the claimants to power, leaving Constantine in control of the Western half of the empire, and Licinius in control of the East.

Orthodox Nicene Christianity would become the essential to securitise central control at the capital, becoming the official State church of the Roman Empire under Constantine. On taking the Imperial office in 306, Constantine I restored Christians to full legal equality and returned property that had been confiscated during the persecution. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built ultimately on Constantine I’s orders at the purported site of Jesus' tomb in Jerusalem and became the holiest place in Christendom, and he is venerated naturally as a Saint. Constantine the son of Constantius I had of course traveled through Palestine at the right hand of Diocletian, and was present at the palace in Nicomedia in 303 and 305. Most notably during Constantine's tenure, he had the Old Saint Peter's Basilica built.

In 325, Constantine I convened the Council of Nicea, effectively the first Ecumenical Council (unless the Council of Jerusalem is so classified). The creed established and affirmed the doctrine that Jesus, the Son, was equal to God the Father, one with the Father, and of the same substance, or co-essential (homoousios in Greek). The Council condemned the teachings of Arius who they declared a heretic, for believing Jesus to be inferior to the Father.

While the Nicene council paved the way for the homoousian doctrine, there remained many closer to the Arian school who attempted to bypass the Christological debate by saying that Jesus was merely like (homoios in Greek) God the father, without speaking of substance (ousia). These non-Nicenes were frequently labeled as Arians (followers of Arius). Arius objected to Alexander's (the bishop of the time) apparent carelessness in blurring the distinction of nature between the Father and the Son by his emphasis on eternal generation. Alexander accused Arius of denying the divinity of the Son and also of being too 'Jewish' and 'Greek' in his thought. Both Arius and Alexander agreed only on rejecting Gnosticism, Manichaeism and Sabellian formulae. The Nicene Creed was created thus as a result of the extensive adoption of the doctrine of Arius far outside Alexandria, in order to clarify the key tenets of the Christian faith.

Starting on 27 February 380, together with Gratian and Valentinian II, Theodosius issued the decree "Cunctos populos", the so-called "Edict of Thessalonica", recorded in the Codex Theodosianus xvi.1.2. This declared the Nicene Trinitarian Christianity to be the only legitimate imperial religion and the only one entitled to call itself Catholic. Other Christians he described as 'foolish madmen' and terminated official state support for them along with all traditional polytheist religions, practices and customs.

On 26 November 380 Theodosius expelled the non-Nicene bishop, Demophilus of Constantinople, and appointed Meletius patriarch of Antioch, and Gregory of Nazianzus, one of the Cappadocian Fathers as patriarch of Constantinople. In May 381, Theodosius summoned a new ecumenical council at Constantinople to repair the schism between East and West on the basis of Nicene orthodoxy. The council went on to define orthodoxy, including the mysterious Third Person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit, who, though equal to the Father, 'proceeded' from Him, whereas the Son was 'begotten' of Him. The council also condemned the Apollonarian and Macedonian heresies. From 389–392 the emperor promulgated the ‘Theodosian decrees’, instituting the ascendance of Catholic Church offices, and abolishing the last remaining expressions of prominent non-Nicene Christianity with the pagan Roman religions (making the holy days into workdays).

Most Popular

-

Metz was a central holding to British and European Royal families, and has a recorded history dating back over 3,000 years; preceding rul...

-

Introduction The Viking were instrumental in early British history and after comparison with a few translations of Voluspa, having n...

Carolingian dynasty

Pippinids

Pippin of Landen

Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia under the Merovingian king Dagobert I from 623 to 629. Also mayor for Sigebert III from 639 until his own death. Pippin (also called the Elder) was lord of a great part of Brabant. He became the governor of Austrasia too when Theodebert II King of that country was defeated by Theodoric II. King of Burgundy, In 613. Through the marriage of his daughter Begga to Ansegisel, a son of Arnulf of Metz, the clans of the Pippinids and the Arnulfings were united, giving rise to Carolingians.

Begga

Bega or Beggue, means the Shining. Born around 620 she died 17 December 692, 693 or 695, daughter of the Frankish mayor of the palace Pepin of Landen. Begga, after the death of her husband Ansegisel, took pilgrimage to Rome, and is said to have built seven chapels in association with the seven main churches of Rome, starting with the Benedictine monastery at Nevelles.

Grimoald

Grimoald (616–657), was the Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia from 643 to 656. He convinced the childless King (Sigebert III) to adopt his son, named Childebert at his baptism. Sigebert eventually had an heir, Dagobert II, but Grimoald feared the fate of his own dynasty and exiled the young Dagobert to either an Irish monastery or the Cathedral school of Poitiers. Upon Sigebert’s death, probably in 651, Grimoald put his son on the throne who Clovis II eventually captured and executed in 657. Grimoald was deposed and executed by the King of Neustria, reuniting the Kingdom of the Franks.

Arnulfings

Arnulf of Metz

Arnold (English) was a Frankish bishop of Metz (582–640) and advisor to the Merovingian court of Austrasia; retired to the Abbey of Remiremont around 628 (a hermitage at a mountain site in the Vosges). Arnulf gave distinguished service under Theudebert II. He distinguished himself both as a military commander and in the civil administration; at one time he had under his care six distinct provinces. Arnulf was married to Doda in 596. Originating to the Arnulfing line as sourced to Zerah, King David, and Joseph of Arimathea.

Ansegisel

(d. 662 or 679) Served King Sigbert III of Austrasia (634-656) as a duke (Latin dux, a military leader) and domesticus. He was killed sometime before 679, slain in a feud by his enemy Gundewin but there are two differing accounts of his death, the other being his death was a hunting accident. Through his son Pepin, Ansegisel's descendants became Frankish kings and ruled the Carolingian Empire.

Chlodulf of Metz

In 657, Chlodulf (d. 696 or 697) became bishop of Metz until 697, the third successor of his father, he held that office for 40 years. During this time he richly decorated the cathedral St. Stephen while in close contact with his sister-in-law Saint Gertrude of Nivelles.

Pepin of Herstal

Frankish statesman and military leader who de facto ruled Francia as the Mayor of the Palace from 680 until death (635-714). Pepin subsequently embarked on several wars to expand his power. He united all the Frankish realms by the conquest of Neustria and Burgundy in 687. In foreign conflicts, Pepin increased the power of the Franks by his subjugation of the Alemanni, the Frisians, and the Franconians. He also began the process of evangelisation of Germany. Around 670, Pepin had married Plectrude, who had inherited substantial estates in the Moselle region.

Grimoald II

Mayor of the Palace of Neustria from 695 (d. 714). He was the second son of Pepin of Heristal and Plectrude. He married Theudesinda (or Theodelinda), daughter of Radbod, King of the Frisians. While en route to visit the tomb of Saint Lambert at Liège, he was assassinated by a certain Rangar, in the employ of his father-in-law. His sons carried on a fight to be recognised as Pepin of Heristal's true heirs, since Grimoald predeceased his father and his bastard half-brother Charles Martel usurped the lands and offices of their father.

Drogo of Champagne

Duke of Champagne by appointment of his father in 690 and duke of Burgundy from the death of Nordebert in 697. He was the mayor of the palace of Burgundy from 695. He married Anstrude, the daughter of Ansflede and Waratton, the former mayor of the palace of Neustria and Burgundy, and also the widow of the mayor of the palace Berthar and they had four sons. Drogo predeceased his father and left the duchy of Champagne to his second-eldest son Arnulf, as the first born Hugh had entered a monastery. Drogo is buried in Metz in Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains.

Theudoald

Mayor of the Palace of Neustria, briefly unopposed in 714 until Ragenfrid was acclaimed in Neustria and Charles Martel in Austrasia (d. 741). Plectrude tried to have him recognised by his grandfather as the legitimate heir to all the Pippinid lands, instead of the illegitimate Charles Martel. His grandmother surrendered on his behalf in 716 to Chilperic II of Neustria and Ragenfrid.

Carolingians

Charles Martel

Frankish statesman and military leader who, as Duke and Prince of the Franks and Mayor of the Palace, was de facto ruler of Francia from 718 until his death (686–741). He restored centralised government in Francia and began the series of military campaigns that re-established the Franks as the undisputed masters of all Gaul. In foreign wars, Martel subjugated Bavaria, Alemannia, and Frisia, vanquished the pagan Saxons, and halted the Islamic advance into Western Europe at the Battle of Tours. Martel was a great patron of Saint Boniface and made the first attempt at reconciliation between the Papacy and the Franks. The Pope wished him to become the defender of the Holy See and offered him the Roman consulship which Martel refused. "the Hero of the Age," & "Champion of the Cross against the Crescent."

Carloman

(716– 17 August 754) was instrumental in consolidating their power at the expense of the ruling Merovingian Kings of the Franks. Called "the first of a new type of saintly king,” he withdrew from public life in 747 to take up the monastic habit; "more interested in religious devotion than royal power, who frequently appeared in the following three centuries and who was an indication of the growing impact of Christian piety on Germanic society”. Gaining support of the Anglo-Saxon

missionary Winfrid (later Saint Boniface), the so-called "Apostle of the Germans,” whom he charged with restructuring the church in Austrasia; Carloman was instrumental in convening the Concilium Germanicum in 742, the first major synod of the Catholic Church to be held in the eastern regions of the Frankish Kingdom. After repeated armed revolts and rebellions, Carloman in 746 convened an assembly of the Alemanni magnates at Cannstatt and then had most of the magnates, numbering in the thousands, arrested and executed for high treason in the Blood Court at Cannstatt.

Pepin the Short

King of the Franks from 751 until his death (714–768). The younger son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel he received ecclesiastical education from the monks of St. Denis. He reformed the legislation of the Franks and continued the ecclesiastical reforms of Boniface. Pepin also intervened in favour of the Papacy of Stephen II against the Lombards in Italy. He was able to secure several cities, which he then gave to the Pope as part of the Donation of Pepin. This formed the legal basis for the Papal States in the Middle Ages. The Byzantines, keen to make good relations with the growing power of the Frankish empire, gave Pepin the title of Patricius. In wars of expansion, Pepin conquered Septimania from the Islamic Ummayads, and subjugated the southern realms by repeatedly defeating Waifer of Aquitaine and his Basque troops, after which the Basque and Aquitanian lords saw no option but to pledge loyalty to the Franks. Pepin was, however, troubled by the relentless revolts of the Saxons and the Bavarians.

Carloman I

King of the Franks from 768 until his death in 771 (b.751). He was the second surviving son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon and was a younger brother of Charlemagne. Carloman's reign proved short and troublesome. The brothers shared possession of Aquitaine, which broke into rebellion upon the death of Pepin the Short; when Charlemagne in 769 led an army into Aquitaine to put down the revolt, Carloman led his own army there to assist, before quarrelling with his brother at Moncontour, near Poitiers, and withdrawing, troops and all. This, it had been suggested, was an attempt to undermine Charlemagne's power, since the rebellion threatened the latter's rule; Charlemagne, however, crushed the rebels, whilst Carloman's behaviour had simply damaged his own standing amongst the Franks. Carloman's position was never strong and he had been left without allies. He attempted to use his brother's alliance with the Lombards to his own advantage in Rome, offering his support against the Lombards to Stephen III and entering into secret negotiations with the Primicerius, Christopher, whose position had also been left seriously isolated by the Franco-Lombard rapprochement; but after the violent murder of Christopher by Desiderius, Stephen III chose to give his support to the Lombards and Charlemagne. Carloman's position was rescued, however, by Charlemagne's sudden repudiation of his Lombard wife, Desiderius' daughter. Desiderius, outraged and humiliated, appears to have made some sort of alliance with Carloman following this, in opposition to Charlemagne and the Papacy, which took the opportunity to declare itself against the Lombards. Carloman died on 4 December 771 while he and his brother Charlemagne were close to outright war.

Charlemagne

Charles the Great (742–814), Latin: Carolus or Karolus Magnus, French: Charles Le Grand or Charlemagne, German: Karl der Große, Italian: Carlo Magno or Carlomagno or Charles I, was the King of the Franks from 768, the King of Italy from 774, and from 800 the first Emperor of the Western Roman Empire. Charlemagne died in 814, having ruled as emperor for just over thirteen years.

Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair, and the Debonaire; was the King of Aquitaine from 781. He was also King of the Franks and co-Emperor (as Louis I) with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. As the only surviving adult son of Charlemagne and Hildegard, he became the sole ruler of the Franks after his father's death in 814, a position which he held until his death, save for the period 833–34, during which he was deposed. In the 830s his empire was torn by civil war between his sons, only exacerbated by Louis's attempts to include his son Charles by his second wife in the succession plans. Though his reign ended on a high note, with order largely restored to his empire, it was followed by three years of civil war.

Lothair I

Lotharius (795 – 29 September 855) was the Emperor of the Romans (817–855), co-ruling with his father until 840, and the King of Bavaria (815–817), Italy (818–855) and Middle Francia (840–855). The territory of Lorraine (Lothringen in German) is named after him. During Lothair's early life, was probably passed at the court of his grandfather Charlemagne. Lothair was sent to govern Bavaria in 815. He first comes to historical attention in 817, when Louis the Pious drew up his Ordinatio Imperii. In this, Louis designated Lothair as his principal heir and ordered that Lothair would be the overlord of Louis' younger sons Pippin of Aquitaine and Louis the German, as well as his nephew Bernard of Italy. Lothair would also inherit their lands if they were to die childless. Lothair was then crowned joint emperor by his father at Aachen. At the same time, Aquitaine and Bavaria were granted to his brothers Pippin and Louis, respectively, as subsidiary kingdoms. Following the murder of Bernard by Louis the Pious, Lothair also received the Kingdom of Italy. In 821, Lothair married Ermengarde (d. 851), daughter of Hugh the Count of Tours.

Charles the Bald

Born on 13 June 823 in Frankfurt, The two years of Charles's reign were 875–877. The three brothers continued the system of "confraternal government", meeting repeatedly with one another, at Koblenz (848), at Meerssen (851), and at Attigny (854). Charles had to struggle against repeated rebellions in Aquitaine and against the Bretons. Led by their chiefs Nomenoë and Erispoë, who defeated the King at the Battle of Ballon (845) and the Battle of Jengland (851), the Bretons were successful in obtaining a de facto independence. Charles also fought against the Vikings, who devastated the country of the north, the valleys of the Seine and Loire, and even up to the borders of Aquitaine.

Louis the Stammerer

Louis le Bègue 1 November 846 – 10 April 879 was the King of Aquitaine and later King of West Francia. He was the eldest son of Charles the Bald and Ermentrude of Orléans. He succeeded his younger brother in Aquitaine in 866 and his father in West Francia in 877, though he was never crowned Emperor. Described "a simple and sweet man, a lover of peace, justice, and religion”, In 878, he gave the countries of Barcelona, Girona, and Besalú to Wilfred the Hairy. His final act was to march against the Vikings a campaign he died during.

Charles III

(17 September 879 – 7 October 929), called the Simple or the Straightforward (from the Latin Carolus Simplex), was the King of Western Francia from 898 until 922 and the King of Lotharingia from 911 until 919–23. the third and posthumous son of Louis the Stammerer by his second wife, Adelaide of Paris. In 893 Charles was crowned but didn’t become the official monarch until the death of Odo in 898. In 911, a group of Vikings led by Rollo besieged Paris and Chartres. After a victory near Chartres on 26 August, Charles decided to negotiate with Rollo, resulting in the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte. For the Vikings' loyalty, they were granted all the land between the river Epte and the sea, as well as Brittany, which at the time was an independent country which France had unsuccessfully tried to conquer. Rollo also agreed to be baptised and to marry Charles' daughter, Gisela.

The nobles, completely exasperated with Charles' policies and especially his favouritism of count Hagano had him deposed in 922 as the Franks revolted raising a Norman army in return during 923 he was defeated on 15 June near Soissons by Robert of Neustria, who however died in the battle. Charles was captured and imprisoned in a castle at Péronne under the guard of Herbert II of Vermandois where he died. Robert's son-in-law Rudolph of Burgundy was elected to succeed him. In 925 the Lotharingians were subsumed into the Kingdom of Germany.

Louis of Lower Lorraine

Last legitimate Carolingian, (c. 980 – after 1012) second son of Charles of Lorraine's three sons and the eldest by his second marriage to Adelaide, the daughter of a vassal of Hugh Capet. Unlike his elder brother Otto, Duke of Lower Lorraine (970–1012) , who inherited their father's duchy of Lower Lorraine; Louis went with his father to France, where Charles fought for the French throne. They both were imprisoned, through the perfidy of Adalberon, Bishop of Laon, by Hugh at Orléans in 991, when Louis was still a child. His father died in prison in or by 993, but Louis was released. It was asserted by Ferdinand Lot that Louis's life after 995 or 1000 was completely unknown, but more recent research has shed some light upon it. It was William IV of Aquitaine who sheltered Louis afterwards, from 1005 until 1012. He opened the Palace of Poitiers to him and treated him as royalty, regarding him as the true heir to the French throne. Louis even subscribed a charter of William's as Lodoici filii Karoli regis. Young Louis drifted, eventually to be utilised by Robert II, Archbishop of Rouen, who was plotting against the Capetians. Louis was imprisoned again, permanently, this time at Sens, where he died.

Paternal Descendants Listing. Generations unto Elizabeth I of England

1. CLODIUS the Long-Haired King of the Salian Franks at Tournai (428 – 448 AD) – Also called Chlodion(Born c395 AD – Died 448 AD at Vicus Helena) He was killed by the Roman commander Flavius Aetius. Clodius was married (c415 AD) to ILDEGONDE of Cologne, the daughter of Marcomir II, King of the Franks at Cologne and his wife Ildegonde of Lombardy, the daughter of Agelmund, King of Lombardy (c380 – 410 AD). Clodius and Queen Ildegonde were the parents of,

2. CHILDEBERT of Cologne King of the Riprarian Franks at Cologne (448 – 483 AD) (Born c425 – Died 483 AD) Childebert was married (c450 AD) to AMALABERGA N (Born c435 – Died before 483 AD), the daughter of Chlodwig, a Frankish chieftain from Cologne. Childebert and Queen Amalaberga were the parents of,

3. SIGEBERT the Lame King of Cologne (483 AD – 509) (Born c452 AD – Murdered in 509 whilst hunting in the forest of Buchau) King Sigebert was murdered by his son Cloderic at the instigation of his kinsman, Clovis I, King of the Salian Franks. Sigebert was married (c470 AD) to THEUDELINDE of Burgundy (Born c455 AD – Died before 509), the daughter of Godesgesil, King of Burgundy (474 AD – 504) and his wife Theudelinde of the Salian Franks, the daughter of Clodius ‘the Long-Haired, King of the Salian Franks at Tournai (428 – 448 AD) Sigebert the Lame and Queen Theudelinde were the parents of,

4. CLODERIC the Parracide Merovingian King of Cologne (509) (Born c473 AD – Murdered 509 at Cologne) He was killed by agents of King Clovis I who had encouraged Cloderic to murder his father Sigebert, for which crime Clovis had him killed. Cloderic was married (c490 – c495 AD) to N of Bavaria, the daughter of Theodo I, Duke of Bavaria and his wife Reginpurga N, and sister to Agilulf. Cloderic and his unnamed queen were the parents of,

5. MUNDERIC of Cologne Merovingian prince of Cologne and Lord of Vitry-en-Perthois (Born c495 – Killed 532) He was executed after leading an unsuccessful rebellion against Theuderic I of Austrasia. Munderic was married (c525) to ARTEMIA of Geneva (Born c510 – Died after 532), the daughter of Bishop Florentinus of Geneva and his wife Artemia. She was the sister of Sacerdos, Archbishop of Lyons, and was of the family of St Gregory, Bishop of Tours. Munderic and Artemia were the parents of,

6. BODEGISEL I Duke in Provence (Born c518 – Died 581) He was the brother of St Gondulf (died 607), Bishop of Tongres. Bodesgesil I was married (before 550) to PALATINA of Troyes (Bron c530 – Died after 562), who was praised by the poet Venantius Fortunatus, the daughter of Gallomagnus, Bishop of Troyes (573 and 581 – 583) Bodesgesil and Palatina were the parents of,

7. BODEGISEL II Duke (dux) of Austrasia and Governor of Aquitaine (Born c550 – Murdered 588 at Carthage in Africa, whilst returning from an embassy to Constantinople) Bodesgesil was married (c580) to ODA of Alemannia (Born c565 – Died 634) later foundress of the abbey of Hamage, near Huy, on the Meuse river), daughter of Leutfrid, Duke of Alemannia and Swabia (553 – 587). As a widow Duchess Oda founded the Abbey of Hamage near Huy on the Meuse River, where she became a nun. Bodesgesil II and Duchess Oda were the parents of,

8. DODA of Austrasia – Also called Oda (Born c587 – Died after 629 at the Abbey of Treves, Austrasia) Buried within the cloister there Doda became the wife (c600 – c605) of ARNULF, Margrave of Scheldt and later Bishop of Metz (611) (Born after Aug 13, 582 – Died Aug 16, 641, at Remiremont in Lorraine), the son of Arnoald I, Margrave of Scheldt and his second wife Blithilde of Austrasia, the daughter of Theudebald, King of Austrasia (547 – 555) Doda and Arnulf separated in order to embrace the religious life, and she became a nun at the Abbey of Treves, taking the religious name of Clotilda. Doda and Arnulf were the parents of,

9. ANISEGAL of Scheldt Merovingian Mayor of Austrasia (632) (Born 612 – Died 662) He was accidentally killed whilst hunting Anisegal was married (c640) to BEGA of Landen (Born 615 – Died Dec 17, 693 at Andenne in Austrasia), the daughter of Pepin I of Landen, Duke (Mayor) of Austrasia, by his wife Iduberga of Aquitaine, the daughter of Grimoald of Austrasia, Duke of Aquitaine and Itta of Gascony. Anisegal and Bega of Landen were the parents of,

10. PEPIN II of Heristal Duke of Austrasia (Born 645 – Died Dec 16, 714) He was married (c675) to Plectrude of Austrasia (Born c659 – Died after 718 in Cologne, and was buried there), the daughter of Count Hugobert of Austrasia and his wife Irmina of Liege, the granddaughter of Dagobert I, King of Neustria and Austrasia (629 – 639). Pepin II had a concubine ALPHAIDA (Alpais) (Born c670 – Died Sept, c720 as a nun at Judoque in Brabant), the daughter of Childebrand who served as a councilor to the Merovingian kings and his wife Emma (Imma). Pepin II and Alphaida were the parents of,

11. CHARLES MARTEL Duke of Austrasia (737 – 741) (Born 690 – Died Oct 22, 741, at Querzy-sur-Oise) Charles was married firstly (c705,) to ROTRUDE of Haspengau (Hesbaye) (Born c690 – Died 724), the daughter of Lantbert II, Count of Haspengau and his wife Chrodelinde of Neustria, the daughter of Theuderic III, King of Neustria (675 – 690) Charles was marrieds secondly (725) to Suanachilde of Bavaria (Born 707 – Died after 755, as a nun at the Abbey of St Marie at Chelles, near Paris), the daughter of Tassilo II, Duke of Bavaria (715 – c720) and his wife Imma of Alemannia. Charles and Duchess Rotrude were the parents of,

12. PEPIN III King of the Franks (751 – 768) (Born 715 – Died Sept 24, 768 at Jupille) Buried within the Abbey of St Denis at Rheims, near Paris Pepin III was married (c740) to BERTRADA of Laon (Born c725 – Died July 12, 783 at the Palace of Choisy at Annecy), the daughter of Carobert, Count of Laon and his wife Bertrada of Neustria, the daughter of Theuderic III, King of Neustria. Pepin III and Queen Bertrada were the parents of,

13. CHARLEMAGNE King (768 – 814) and first Emperor of the Franks (800 – 814) (Born April 2, 746, at Ingelheim, near Mainz – Died Jan 28, 814, at Aachen) Buried at Aachen Charlemagne was married thirdly (771) to HILDEGARDE of Vinzgau (Born 757 – Died April 30, 783 at the Abbey of Kaufingen, Thionville), the daughter of Gerold I, Count of Vinzgau and Kraichagu, and Prefect of Bavaria by his wife Emma of Alemannia, the daughter of Nebi (Hnabi), Duke of Alemannia. Charlemagne and Queen Hildegarde were the parents of,

14. LOUIS I the Pious King of Aquitaine and Emperor of the Franks (814 – 840) (Born Aug, 778, at the villa of Chasseneuil, near Agenois – Died June 20, 840, at the Palace of Ingelheim, near Mainz) Louis was married firstly (794 at Orleans) to Ermengarde of Hesbaye (Born c780 – Died Oct 3, 818, at Angers in Anjou), the daughter of Ingelramnus, Count and Duke of Hesbayne (Haspengau) and his wife Rotrude, probably the daughter of Thurincbert, Count of Breisgau. Emperor Louis married secondly (Feb, 819) to JUDITH of Altdorf (Born 805 – Died 843 at Tours) the daughter of Welf II, Count of Altdorf and Swabia and his wife Heilwig of Engern, the daughter of Bruno II, Count of Engern. Louis I and Empress Judith were the parents of,

15. GISELA of Neustria Imperial Princess (Born 820 – Died after July 1, 874) Buried in the Abbey of St Calixtus at Cysoing Gisela was married (836) to EBERHARD, Duke of Friuli (Born c805 – Died 866, and buried within the Abbey of St Calixtus), the son of Unruoch of Ternois, Duke of Friuli and his wife Ingeltrude of Paris, the daughter of Leuthard of Paris, Count of Fezensac. Gisela and Duke Eberhard were the parents of,

16. INGELTRUDE of Friuli (Born c839 – Died after July 1, 874) Buried within the Abbey of St Calixtus at Cysoing Ingeltrude was married (c853) to HENRY of Grabfeldgau (Born c830 – Died Aug 28, 886 outside Paris, being killed in battle, and was buried within the Abbey of St Medard at Soissons), Duke of Franconia and Austrasia, Margrave of Nordmark and Count in the Saalgau, the son of Poppo I, Count of Grabfeldgau and Saalgau. Duchess Ingeltrude and Duke Henry were the parents of,

17. HEDWIG of Grabfeldgau (Born c854 – Died Dec 24, 903) Buried within the Abbey of Gandersheim, near Goslar Hedwig was married (869) to OTTO I the Illustrious (Born 836 – Died Nov 30, 912, and buried within the Abbey of Gandersheim), Duke of Saxony (880 – 912), the son of Luidolf, Duke of Saxony and his wife Oda of Franconia, the daughter of Billung I of Franconia, Count of Thuringia and his wife Aeda of Neustria, the granddaughter of the Emperor Charlemagne. Duchess Hedwig and Otto were the parents of,

18. HENRY I the Fowler Henry I, Duke of Saxony (912 – 936) and Holy Roman Emperor (919 – 936) (Born 876, at Memleben – Died July 12, 936, at Memleben) Buried within the Basilica of St Servatius within the Abbey of Quedlinburg Henry was married firstly (905) to Hathburga of Merseburg (Born c877 – Died after 909), the widow of NN (an unidentified nobleman), and the daughter of Count Erwin of Merseburg. Hathburga had apparently taken vows as a nun at the Abbey of Altenburg when Prince Henry married her. Bishop Sigismund of Halberstadt denounced the marriage as unlawful, and the church forced the couple to separate (909). Their only child Thankmar was considered illegitimate and thus rendered ineligible to wear the Imperial crown. Henry then remarried secondly (911, at the Abbey of Nordhausen, Saxony) to MATHILDA of Westphalia (Born 897 – Died March 14, 968, at the Abbey of Quedlinburg, near Halberstadt in Germany, and was interred within the Basilica of St Servatius at Quedlinburg), the daughter of Theodoric, Count of Westphalia and Ringelheim and his wife Reginlinda of Friesland, the daughter of Godfrey of Friesland, King of Haithabu. Emperor Henry and Empress Mathilda were the parents of,

19. GERBERGA of Saxony (Born 913 at Abbey of Nordhausen, Saxony – Died May 5, 984, at Rheims, Marne) Buried within the Chapel of St Remi in the Abbey of St Denis at Rheims Gerberga was married firstly (929) to GISELBERT (Born 890 – Died Oct 2, 939, at Echternach), Duke of Lorraine (928 – 939) and Lay Abbot of Echternach in Luxemburg (915 – 939), the son of Rainer I of Hainault, Duke of Lorraine (900 – 916) and his second wife Alberada of Mons, the daughter of Count Adalbert (Albert) of Mons. Duchess Gerberga was married secondly (939) to Louis IV (Born Sept 10, 921 at Laon, Aisne – Died Sept 10, 954 at Rheims, Marne, and buried within the Chapel of St Remi in the Abbey of St Denis at Rheims), King of France (936 – 954), the son of Charles III the Simple, King of France (893 – 922) and his second wife Otgifa of England, the daughter of Edward the Elder, King of England (899 – 924). Gerberga and Giselbert of Lorraine were the parents of,

20. ALBERADA of Lorraine (Born c930 – Died March 15, 973) Alberada was married (before 947) to RAINALD of Roucy (Born c920 – Died May 10, 967, and was buried within the Abbey of St Remi at Rheims), the son of Ragnvald, a Norse invader who settled in Burgundy. Alberada and Count Rainald were the parents of,

21. ERMENTRUDE of Roucy (Born c954 – Died March 8, 1005) Eremntrude was married firstly (c970) to Alberic II (Born c935 – Died 980), Count of Macon (965 – 980), the son of Lietaud II, Count of Macon (945 – 965) and his first wife Ermengarde of Chalons. Ermentrude then became the first wife (982) of OTTO I WILLIAM of Burgundy (Born c961 – Died Oct 21, 1026, and was buried within the Abbey of St Benigne at Dijon), King of Lombardy and Count of Macon (Born c961 – Died 1026), the son of Adalbert of Ivrea, King of Lombardy and his wife Gerberga of Chalons (later the wife of Duke Eudes of Burgundy). Queen Ermentrude and Otto William were the parents of,

22. RAINALD I of Burgundy Count of Burgundy and Macon (1026 – 1057) (Born c990 – Died Sept 4, 1057) Rainald was married firstly (1016) to ADELIZA of Normandy (Born 1000 at Rouen – Died after July 1, 1037), the eldest daughter of Richard II, Duke of Normandy (996 – 1026) and his first wife Judith of Rennes, the daughter of Conan I the Red, Duke of Brittany. Rainald I and Countess Adeliza were the parents of,

23. WILLIAM II the Great of Burgundy Count of Burgundy and Macon (1057 – 1087) (Born c1024 – Died Nov 12, 1087) – Nicknamed Tete-Hardi William was married (c1150) to STEPHANIE of Metz (Born c1035 – Died 1109), the heiress of the county of Longwy, daughter of Adalbert III of Metz, Duke of Upper Alsace and Count of Longwy, and his wife Clemencia of Foix, the daughter of Bernard Roger of Bigorre, Count of Foix. William II and Countess Stephanie were the parents of,

24. ERMENTRUDE of Burgundy (Born c1055 – Died after March 8, 1105) Ermentrude became the wife (before 1070) of THIERRY II (Born c1045 – Died Jan 2, 1105), Count of Bar and Montbeliard (c1076 – 1105), the son of Louis II, Count of Bar and Montbeliard, and his wife Sophia of Bar, heiress of the county of Bar, the daughter of Frederick II, Duke of Upper Lorraine and Count of Bar and his wife Matilda of Swabia, the daughter of Hermann II, Duke of Swabia (997 – 1003). Countess Ermentrude and Thierry II were the parents of,

25. RAINALD I of Bar Count of Bar-le-Duc and Mousson (1026 – 1050) (Born c1090 – Died June 24, 1150) He founded the Abbey of Rieval and the Priory of Moncon Rainald was married firstly (c1108) to GISELA of Lorraine (Born c1090 – Died c1126), the daughter of Gerhard I of Lorraine, Count of Vaudement by his wife Hedwig of Egisheim, the daughter of Gerard III, Count of Egisheim. Rainald was married secondly (c1127) to NN, the widow of Rainald, Count of Toul, whose identity remains unknown. Rainald I and Countess Gisela were the parents of,

26. RAINALD II of Bar Count of Bar (1150 – 1170) (Born c1115 – Died July 25, 1170) Rainald was married (1155) to Agnes of Champagne (Born c1138 – Died Aug 7, 1207), the daughter of Theobald II, Count of Champagne (V of Blois-Chatres) and his wife Matilda of Carinthia, the daughter of Engelbert II, Duke of Carinthia and his wife Uta of Passau, the daughter of Ulrich, Count of Passau. Rainald II and Countess Agnes were the parents of,

27. THEOBALD I of Bar Count of Bar (1170 – 1214) and of Briey and Luxemburg (Born 1158 – Died Feb 2, 1214) Buried within the Abbey of St Michael Theobald was married firstly (c1174) to Adelaide of Looz (Laurette) (Born c1150 – Died c1184), the widow of Gilles, Count of Clermont, and the daughter of Louis I, Count of Looz, and his wife Agnes of Metz, the daughter of Volmar V, Count of Metz. Theobald married secondly (c1185) to ISABELLE of Bar (Ermesent) (Born c1158 – Died c1192), the widow of Anseau II, Seigneur of Trainel, and the daughter of Guy, Count of Bar-sur-Saone and his wife Peronelle de Chacenay, the daughter of Ansery de Chacenay, Baron de Chacenay of Champagne. Theobald was married thirdly (1193) to Ermesinde of Luxembourg (Born July, 1186 – Died May 9, 1246) sovereign Countess of Luxemburg and Namur, the daughter of Henry IV the Blind, Count of Luxembourg-Namur and his second wife Agnes of Gueldres, the daughter of Henry II, Count of Gueldres and Zutphen and his wife Agnes von Arnstein. Countess Ermesinde remarried to Waleran IV, Count of Limburg. Theobald and his second wife Countess Isabelle were the parents of,

28. HENRY II of Bar Count of Bar (1214 – 1239) and Count of Luxemburg and Namur (Born c1188 – Died Nov 13, 1239 at Gaza, Palestine, being killed in battle) Henry was married (1219) to PHILIPPA of Dreux (Born 1192 – Died March 17, 1242), heiress of the seigneurie of Toucy, the daughter of Robert II, Count of Dreux and his second wife Yolande of Coucy, the daughter of Raoul I of Marle, Seigneur of Coucy and his first wife Agnes of Hainault, the daughter of Baldwin IV, Count of Hainault. Henry II and Countess Philippa were the parents of,

29. THEOBALD II of Bar Count of Bar (1239 – 1297) (Born c1221 – Died 1297) Theobald was married firstly (c1245) to Jeanne of Dampierre (Born c1227 – Died c1275), the widow of Hugh III, Count of Rethel, and daughter of Margaret, Countess of Hainault and Flanders, by her second husband, William II, Count of Dampierre. Theobald was married secondly (c1278) to JEANNE of Toucy (Born c1261 – Died c1317), the daughter of Jean I, Vicount of Toucy and his wife Emma de Laval, the daughter of Guy VI, Seigneur de Laval. Theobald II and Jeanne of Toucy were the parents of,

30. ISABELLA of Bar (Born c1280 – Died c1320) Isabella was married (before 1300) to GUY of Flanders (Born c1275 – Died 1338), Lord of Termonde, the son of William of Flanders, Lord of Termonde and his wife Alice of Clermont, the daughter of Raoul, Count of Clermont. Guy was the grandson of Count Guy of Flanders (1229 – 1305). Isabella and Guy were the parents of,

31. ALIX of Flanders (Born c1310 – Died 1346) Alix was married (c1326) to JEAN I (Born c1305 – Died 1364), Count of Luxembourg-Ligny-Roussy, the son of Waleran II, Count of Luxembourg-Ligny and his wife Guiotte de Hautbourdin, the daughter of Jean VI de Hautbourdin, Seigneur de Lille and his wife Beatrice of Clermont, the daughter of Simon II, Count of Clermont. Alix and Jean I were the parents of,

32. GUY VI of Luxembourg-Ligny Count of Luxemburg-Ligny (1364 – 1371) and Chatelain of Lille in Flanders (Born c1329 – Killed 1371, at the battle of Baesewilder) Guy was married (c1354) to MATILDA of Chatillon (Born c1330 – Died 1378), sovereign Countess of St Pol, the only child and heiress of John I of Luxembourg, Count of St Pol and his wife Jeanne de Fiennes, the daughter of Jean, Seigneur de Fiennes, and sister of Robert ‘Moreau’ de Fiennes, Constable of France (died c1385) Guy VI and Countess Matilda were the parents of,

33. JEAN II of Luxembourg Count of St Pol (1378 – 1397) and Seigneur de Beaurevoir (Born c1356 – Died 1397) He was married (c1379) to MARGEURITE d’Enghien (Born c1362 – Died 1393), the daughter of Louis d’Enghien, Count of Brienne, and his wife Isabella, Countess of Brienne and Leece, the daughter of Walter V, Duke of Athens and Count of Brienne. Jean II and Countess Margeurite were the parents of,

34. PIERRE I of Luxembourg Count of St Pol (1415 – 1433) (Born c1380 – Died 1433) He was married (c1405) to MAGARET del Balzo (Born c1390 – Died 1469), the daughter of Francesco del Balzo (des Baux), Duke of Andria and his second wife Sueva di Orsini (Justina), the daughter of Nicholas di Orsini, Count di Nola and Senator of Rome. Pierre and Countess Margaret were the parents of,

35. JACQUETTA of Luxembourg (Born 1416 – Died May 30, 1472) Jacquetta was married firstly (April 20, 1433, at Therouanne) as his second wife, to John Plantagenet, Prince of England, Duke of Bedford (Born June 30, 1389 – Died Sept 14, 1435 at Rouen, France), the son of Henry IV, King of England (1399 – 1413) and his first wife Lady Mary de Bohun, the younger daughter and co-heiress of Humphrey de Bohun, 7th Earl of Hereford and Essex. Duchess Jacquetta was married secondly (secretly) (before March 23, 1436) to Sir RICHARD WOODVILLE (born c1405, executed by the Lancastrians at Kenilworth, Aug 12, 1469, after the battle of Edgecot), the first Earl of Rivers, the son of Richard Woodville of the Mote in Maidstone, Kent, and his wife Mary Bedleygate. Duchess Jacquetta and Richard Woodville were the parents of,

36. LADY ELIZABETH WOODVILLE (Born 1437 at Grafton Regis, Northamptonshire – Died June 7, 1492, at Bermondsey Abbey, London) Buried within St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in Berkshire Elizabeth was married firstly (c1452) to Sir John Grey of Groby (Born 1432 – Killed by the Yorkists 1461), the son of Sir Edward Grey of Groby, 7th Baron Ferrers, and his wife Elizabeth, Baroness Ferrers, the daughter and heiress of William, 6th Baroness Ferrers. Elizabeth was married secondly (secretly) (May 1, 1464, at the manor of Grafton Regis) to EDWARD IV 9Born April 28, 1442, at Rouen in Normandy – Died April 9, 1483, at Westminster Palace in London, and was buried in St George’s Chapel at Windsor) King of England (1461 – 1483), the son of Richard, Duke of York and his wife Lady Cecilia Neville, the daughter of Sir Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland. Queen Elizabeth and Edward IV were the parents of,

37. ELIZABETH of York Princess of England (Born Feb 11, 1465, at Westminster Palace, London – Died in childbirth (Feb 11, 1503, at the Tower of London) Buried within Westminster Abbey, London Elizabeth was married (Jan 18, 1486, at Westminster Abbey, London) to HENRY VII (Born Jan 28, 1457, at Pembroke Castle in Wales – Died April 21, 1509, at Richmond Palace, Surrey, and was buried within Westminster Abbey), King of England (1485 – 1509), the only son of Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, by his wife Lady Margaret Beaufort, the only child and heiress of John Beaufort, first Duke of Somerset and his wife Margaret de Beauchamp (later wife of Lionel, 6th Baron Wells), the widow of Sir Oliver St John, of Bletsoe in Bedfordshire, and daughter of John de Beauchamp, 3rd Baron Beauchamp of Bletsoe. Queen Elizabeth and Henry VII were the parents of,

38. HENRY VIII of England King of England (1509 – 1547) (Born June 28, 1491, at Greenwich Palace, Kent – Died Jan 28, 1547, at Whitehall Palace, London) Buried within St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle in Berkshire) Henry VIII was married many times and bore a single son with Queen Jane Seymur, who died from child birth complications. Henry VIII and Jane Seymour were the parents of;

39. Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) born at Hampton Court Palace in Midlesex, King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. The last King of the Tudor dynasty Edward died at the age of 15 at Greenwich Palace on 6 July, from a suspected tumor of the lung.

40. MARY I of England Queen regnant of England July 1553– Nov 1558 (Born 18 February 1516 at the Palace of Placentia in Greenwich, Died 17 November 1558). Daughter of Henry VIII and Queen Catherine of Aragon. Married to Philip of Spain, who was Prince Consort, son of Charles V and Infanta Isabella of Portugal. Mary had no heirs and over religious difference seized the Throne from Lady Jane Grey, who was pronounced successor by Edward upon his death, only holding title for 9 days. Mary was Buried 14 December 1558 Westminster Abbey, London.

41. ELIZABETH I of England Elizabeth Tudor, Queen regnant of England (1558 – 1603) (Born Sept 7, 1533, at Greenwich Palace, Kent – Died March 24, 1603, at Richmond Palace, Surrey. Daughter of Henry VIII and Queen Anne Boleyn. Buried within Westminster Abbey, London Remained unmarried until death which brought the Tudor Dynasty to an end(1485 – 1603).

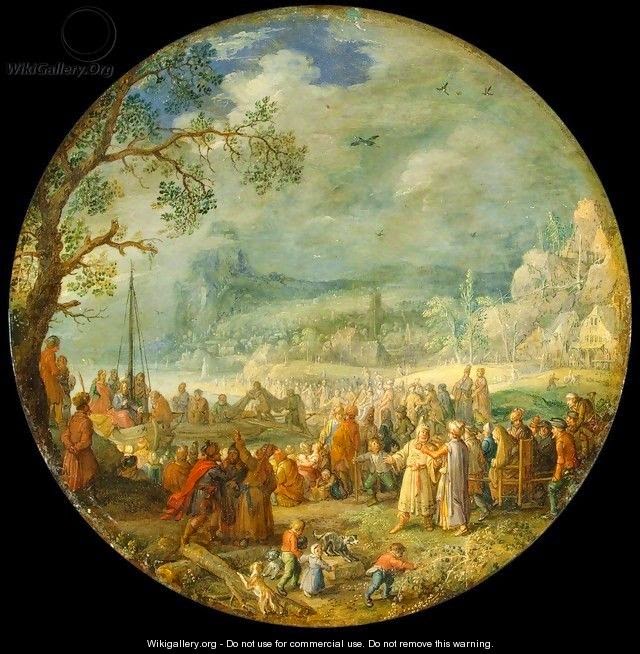

Sermon of Christ at the Lake Genezareth

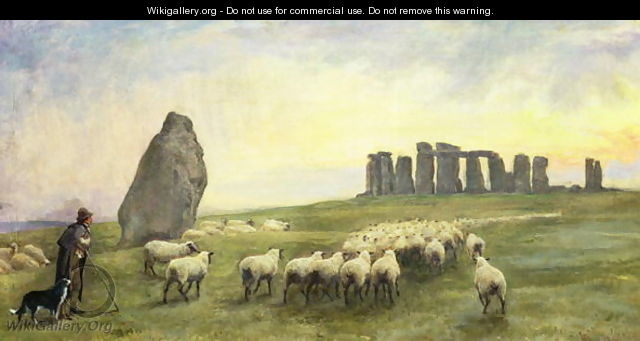

Edgar Barclay's Stonehenge, 1891

C.Verrusson's Haghia Sophia

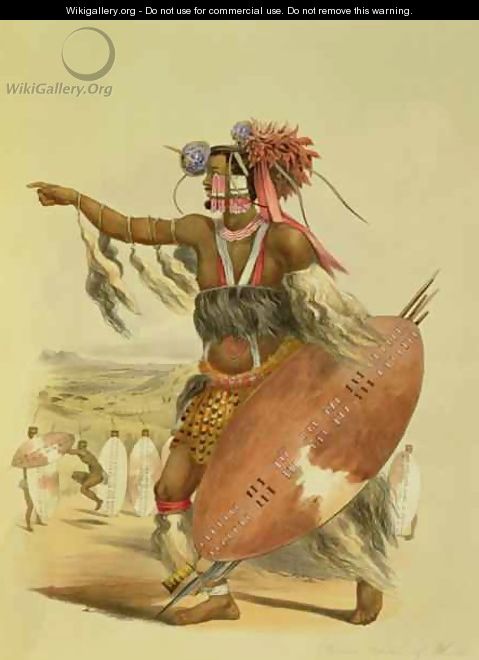

Utimuni the Zulu nephew of Chaka

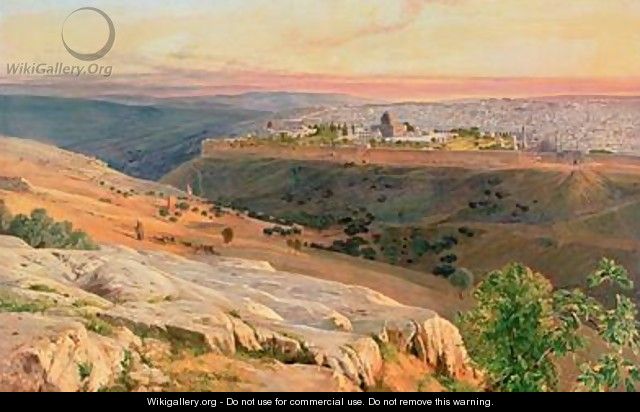

Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives by Edward Lear

Laconian bronze banqueter 530-500 BCE. Dodona British Museum

The Battle of Oroi-Jalatu